Epic Fail #3: Copy-Pasting Code With Unicode Quotes

For Web Application Security class last year, most of the final exam was an open-book, open-internet practical: we were given a remotely hosted web application to play with, and we had to obtain flags. No flag meant no mark.

My prepwork involved making a PDF document using Latex containing all the written notes I needed. This was of course supplemented by other resources such as my archive of homework solutions, lecture slides, textbooks, etc. A key component of that Latex document of course was code that could be copy-pasted when needed.

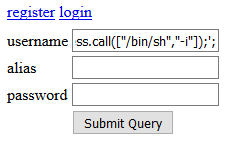

The problem with that code, however, is that it’s not like a program you’re meant to compile and run locally, otherwise a compiler or interpreter would’ve caught the issue and issued the relevant warnings for the problem, allowing it to be resolved quickly. Instead, the code is often pasted directly into input text fields of a web page like so:

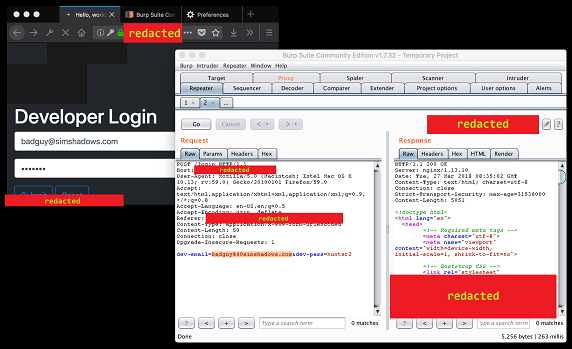

Or, the significantly better method of using Burp Repeater and other such tools:

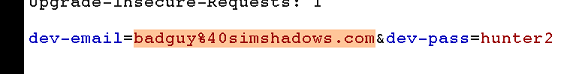

In the above screenshot, the raw input data can be observed and modified here:

After sending off the input data to the remote server, feedback produced by the server may be limited and you may have to infer the web application’s state from minimal information. After all, web servers and applications are ideally designed to withstand attacks from the outside which look to coax the app/server into doing something to the attacker’s advantage. Intentionally hiding unnecessary information about the system is one of many tricks defenders use as part of the overall defense strategy.

In reality, the amount of relevant feedback emitted by the web server/application can vary significantly, depending on many aspects of the system. However, the fact still remains: A lot of the time, you’re swinging in the dark until you catch something. You may catch plenty, you may catch none, or you may even catch bait or misleading responses.

In my case, despite having revised and practiced extensively before that final exam practical, I got zero flags. Even more painful was how I spent the two hours trying every trick and variation I knew, and feeling like I knew exactly what the solution should be for all flags that didn’t require knowledge of other flags, yet nothing did anything interesting. I kept thinking I missed some detail about the web application and continued to think along those lines.

After the exam was over, I got a colleague to show me a flag. She got two of them instantly. (I think the application was taken down before we could try more flags.)

That afternoon, I found my text document full of payload code I made during the exam. A lot of the quotation marks were found to be Unicode, as an artifact of my PDF document compiled from Latex. All my payloads were based off text copied from that PDF document. Although I can’t confirm, that was most likely the reason my payloads failed to make the web application budge one bit. If I just used ASCII quotation marks, I would’ve gotten at least a few flags.

Unicode Quotation Marks? What?

By Unicode quotation marks, I’m referring to the quotation marks that are not part of ASCII.

The ASCII quotes (including the grave mark) are:

Hex Unicode Raw Description

----------------------------------------------------

0x22 U+0022 " QUOTATION MARK

0x27 U+0027 ' APOSTROPHE

0x60 U+0060 ` GRAVE ACCENT

The quotation characters above are the ones that are typically intended for the computer to parse with special meanings that are important in all aspects of a programmer’s work.

The following is a subset of what I consider to be the “Unicode quotation marks”:

Unicode Raw Description

----------------------------------------------------

U+2018 ‘ LEFT SINGLE QUOTATION MARK

U+2019 ’ RIGHT SINGLE QUOTATION MARK

U+201C “ LEFT DOUBLE QUOTATION MARK

U+201D ” RIGHT DOUBLE QUOTATION MARK

(Note: Technically, ASCII is a strict subset of Unicode blocks, hence ASCII characters are also Unicode characters, but Unicode characters are not all ASCII characters.)

These “Unicode quotation marks” are intended to be more typographically accurate than ASCII quotes (which appear straight compared to the curliness of Unicode quotes). They are not typically meant to be interpreted by computers in place of Unicode quotes.

In my case, the ASCII quotes I used in the Latex document were converted to Unicode quotes in the compiled PDF. Word processors (such as Microsoft Word) will often similarly convert quotes. Other applications (such as email) may also convert quotes. All of this is done to make the final document visually pleasing and typographically correct (much to the detriment of computing professionals out there).

You may have also noticed that this blog post’s quotation marks may have been converted into Unicode quotation marks (except in code blocks). Assuming I haven’t changed things too much since the time of writing, these blog posts are sourced from files written in Jekyll Markdown, and here, I use ASCII quotes.

Further reading:

- Raymond Chen (2009). Smart quotes: The hidden scourge of text meant for computer consumption. https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/oldnewthing/20090225-00/?p=19033

Recommendations

Even beyond things like rendered PDFs, Microsoft Word, and HTML web pages, you may run into the issue in simple plaintext files (such as if someone simply copy-pasted text in from Microsoft Word or a PDF, like during my web application security exam). Unicode quotes can come in from anywhere when you least expect it.

This is one of those things where the best you can do is be aware and have it at the back of your mind, and hopefully this blog post has given you that awareness. Next time you run into a cryptic problem with seemingly no obvious reason, Unicode quotes may be worth considering.

Beyond Unicode Quotes

It really doesn’t take much to go beyond and find more problems related to using different characters that look visually similar (or the exact same). For instance, a popular example of this problem set is the “GREEK QUESTION MARK” (U+037E)”. This character is visually similar to the semicolon character (;), and is often used as an example of a prank that can be used on programmers (such as this Stack Overflow post).

In the context of security, the exploitation of such a mechanism is called a homograph attack. IDN homograph attacks for instance can be used to trick users into believing they’re browsing www.apple.com when in fact they are browsing xn–80ak6aa92e.com (that link is not malicious at the time of writing, and was made to harmlessly illustrate the dangers of this IDN homograph vulnerabilities).

Further Reading:

- Xudong Zheng (2017). Phishing with Unicode Domains. https://www.xudongz.com/blog/2017/idn-phishing/

- Jovi Umawing (2017). Out of character: Homograph attacks explained. https://blog.malwarebytes.com/101/2017/10/out-of-character-homograph-attacks-explained/

As for me, I took a supplementary exam for web application security class several weeks after the original exam. Needless to say, I made doubly sure I had properly formatted (with ASCII characters) code the second time around. My unicode quotes problem was no more.